(Pictured above: Some good looking guy signing the Peace Wall. Read Peace Wall as an enormous divide between communities that signifies the safety now experienced in Belfast and how far these communities still must come.)

It is no exaggeration that Belfast was one of the most war torn areas of the late 20th Century. Local terrorist organizations sprang into action in response to escalating tensions between 1968-1971. The story here mirrors the story in Derry. But that city is a tiny hamlet compared to Belfast. Shove a million people into a rain cloud, some who bleed green and others for the queen, a football pitch’s worth of British tanks and troops, with an insatiable eye-for-an-eye mentality. You have 70s-90s Belfast.

The violence was unparalleled. As Michael Rock (today’s tour guide) puts it, “If someone was killed on a Catholic Street by 10 AM, someone in a Protestant neighborhood would be dead by 12.” Everyone was a target. Walls were constructed to keep communities separate. Like any city aspiring to be the best, the walls had to be built higher and higher. You know, to deter the bricks, bottles, fireworks launched from landing in their backyards.

It is obvious when you are in a Protestant Unionist community in Northern Ireland. Its vivid. The awnings and shops are blue and red. The streets are adorned with red, white and blue streamers, the light posts hoist the Union Jack. A couple reasons. The Queen’s jubliee (currently visiting Northern Ireland, Mr. McGuinness tomorrow). The marching season is amping up. Check out the pictures of the bonfire preparations!

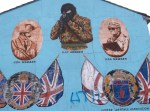

Each community has their murals. It seems the Catholic Nationalists made a concerted attempt to give their areas a face lift. The images are less violent. Their causes slightly more universal (read: Palestine). Their symbolism notably lacks gun wielding, masked gunmen. It seems like the Protestant Unionists are getting the message. Sandy Row’s murals are almost completely devoid of the violent imagery. Instead they tell a tale of the community’s working class heart. But in the Shankill neighborhoods, along the Peace Wall yours truly is elegantly signing above, imagery of fallen UDA assassins still exists and some memorials are down right aggressively militaristic. When photographing one of them, a few children in this beat-down neighborhood shouted out: Everyday I’m UDA. They were holding beebee guns. They pointed them at the taxi as we toured their neighborhood. It is this sense of intimidation I will be trying to erase, in myself, as I walk through to Shankill tomorrow.

Also on the docket: A visit with Sean Montgomery and the Skegoneill-Glandore Community Center (where Protestant and Catholic communities meet) to see what connections can be made for the young when there is not an enormous Interface (Peace Wall) between them. And a walk to the Ardoyne part of the Catholic neighborhood, The Falls. There I will begin my relationship with the group recording and facilitating the Interface Diaries. Compelling and exciting to introduce to my students.